Guidelines for the Clean

The Proper Position for Receiving The Bar in the Clean

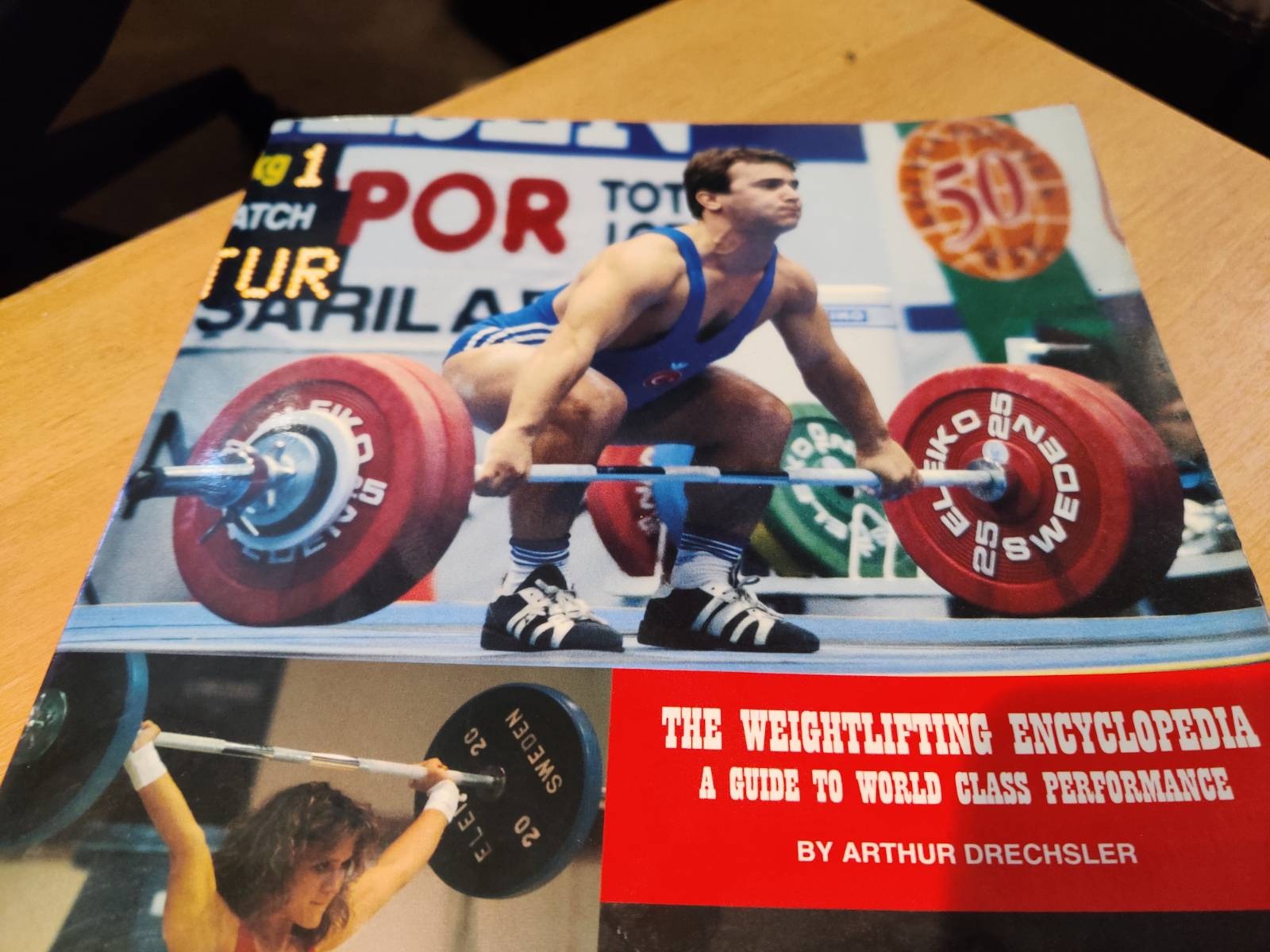

Raising the elbows high and with substantial speed (a movement known as “whipping the elbows”) and landing with the torso, feet and knees in proper position are the keys to receiving force in the clean. The elbow whip helps to keep the upper body properly rigid .(This subject is covered in greater detail in a later section of this chapter.) Proper foot positioning consists of placing the feet so that the best combination of stability and strength is achieved. This will normally be a position with the feet at an angle between 30’ and 60’, although some use an angle that is considerably longer or smaller with great success. The distance between the lifter’s heels is typically between 10“ and 18“.

The correct foot position for a given athlete is one in which the lifter’s lower back can remain arched, or at least relatively flat, and the upper body can be held upright (i.e., nearly perpendicular to the floor). Some lifters have no difficulty in achieving such a position with virtually any foot position. But for most lifters a wider stance and/or a greater angle between the feet help them to achieve an upright position of the torso with the back arched. A wider stance also lowers the lifter’s center of gravity and provides the lifter with a wider base of support. These factors lead to a more efficient and stable receiving position.

If a wider foot position is so advantageous, why don’t all lifters place their feet as wide as possible? The primary disadvantage of a wide foot position and/or a large angle between the feet is that this kind of position can place extra stress on the hip joints. This will be experienced by the lifter either as sort of an “unhinging” at the hips or as actual discomfort. The unhinging is somewhat difficult to describe, but the lifter feels as though all or most of the strain of the supporting effort is on the hip joint and the muscles, tendons and ligaments of the knees and ankles are under relatively little stress. Another sure sign is that the lifter feel a rotation of the femur in the hip joint during the early stages of rising from the squat position. Healthy hip joints play a major role in weightlifting success and in general human locomotion. It is extremely important to protect the hip joint from undue strain. Therefore, it is a good idea to place the feet wide enough to achieve as solid and upright torso position but no wider.

For the lifter who is extremely flexible, there is one other constraint on foot spacing. Such a lifter can find that with the feet in a wide position his or her hips actually travel well past the heels in the deep squat position, particularly when the bar is coming down with substantial force. This causes the lifter’s lower back to lose its arch and generally places the lifter in a unstable position for receiving the weight of the bar. Placing the feet in a narrower position (one in which the lifter’s buttocks touch the lifter’s ankles in the deep squat position) will enable the lifter to control the bar more effectively.

As was suggested earlier, turning the feet outward (i.e., increasing the angle between the feet) tends to cause the lifter to spread the knees and to attain a more upright position and arched back with the same spacing between the heels. The correct knee position is generally directly over the foot; placing the knees too far outside the feet will place a great strain on the hip joint and adductor muscles of the legs, and turning the knees too far inside the feet will tend to place a twisting kind of strain on the knee joints.

Apart from discomfort reported by the lifter, the clearest indicator of improper foot and leg positioning is lateral movement of the knees and/or feet when the bar is received by the lifter. The knees should be functioning essentially as a hinge when the bar is received by the lifter, and the feet should be flat on the platform. Lifters who are on their toes at any point during the supported squat under should be carefully observed in terms of foot positioning. There are several causes for the lifter being on his or her toes during the squat under, but the possibility of improper foot positioning should be ruled out. Lifters whose feet are supported on their inner edge of the foot (i.e., the outer edge of the foot is raised from the platform) while descending into the squat position or while receiving the force of the bar are almost certainly positioning their feet and legs improperly. Similarly, when the lifter’s knees are seen to wobble while the bar is being received (when they move laterally in addition to merely bending), the lifter’s positioning needs to be improved. Improvements in the lifter’s receiving position can be achieved through conscious repositioning of the feet. If that fails to achieve a satisfactory result (it almost inevitably yields an improvement of some kind), attention needs to be paid to the lifter’s flexibility and the height of the heel in the lifter’s shoe.

Apart from body positioning, the key to receiving and controlling the force of the bar lies in the action of the legs. In the squat position the lifter’s arms and torso play a relatively small role in stopping the downward progress of the bar. They must be held in a proper position so that they do not give when the bar is received, but their primary role is to transfer the force of the bar to the lifter’s legs. The legs function like shock absorbers when the bar is being received. Therefore, the arms and torso should assume a rigid position as soon as possible during the squat under, and the legs should assume the crucial role of stopping the downward progress of the bar. The legs should begin to interact with the bar as soon as possible because every split second during which the bar has no support causes it to pick up downward speed and become more difficult to control. Nevertheless, if the lifter attempts to apply a braking force too vigorously or while he or she is in an unfavorable anatomical position, the muscletendon unit of the thighs will be subjected to unnecessary trauma, and the elastic qualities of those muscles will not be effectively utilized in assisting the lifter to recover from the low squat position

In short, the lifter should use the legs early and actively to bring the bar under control but should then use a sort of natural rebound from the low position to assist in the lifter’s recovery. No effort to stop short or even to significantly slow down the bar should be made unless the lifter is at or near his or her lowest position in the squat. At that point the knee, hip and ankle joints of the body and all of the muscle-tendon units that support them are being used in concert to stop the bar and to support one another (e.g., the pressure of the back of the thighs against the calves). If, in contrast, the lifter catches the bar with the thighs and calves at a near 90’angle and attempts to stop immediately. great and unnecessary stress will be placed almost exclusively on the muscle-tendon unit at the front of the thighs. In addition, while the lifter could have employed the elastic qualities of the quadriceps muscles to stand up from the squat position, he or she will be recovering from a dead stop.

The preceding discussion is not meant to suggest that he lifter “crashes” into the deep squat position at all times, offering little or not resistance to the bar. Each lifter will need to learn the proper balance of control and using the natural flow of the muscles in order to feel a relatively smooth receiving of the bar’s force and an almost seamless transition into the recovery from the squat position

Elbow “whip” (the rapid movement of the elbows from a position above the bar during the pull to a position for receiving the bar in the clean) is a very important element of receiving the bar effectively in the clean, and a number of aspects of it are often neglected when it is taught. If you are observing a lifter from his or her left side, elbow whip consists of a rapid clockwise turning of the elbows around the bar from a position above or just behind the bar to one in which the elbows are well forward of the bar, preferably so that the underside of the lifter’s upper arm is at or near the nine o’clock position, or even above it (e.g., at ten o’clock). Coaches often talk about keeping the elbows over the bar during the later stages of the pull so that the bar will remain close to the body while the elbows are turned from the pull to the racking position on the chest. I have never been persuaded of the usefulness of this method of describing the motion of the arms to the lifter, because the elbows never bend while they are positioned over the bar in the pull for the clean (or the snatch for that matter). The arms do not bend until the lifter is descending under the bar, and at that point the elbows are behind the bar. Sometimes telling the lifter to keep the elbows over the bar will prevent a tendency to “reverse curl” the bar (i.e., keep the elbows at a fixed position near and in line with the torso and simply pull the bar to the shoulders with the arms), so this instruction is certainly worth a try. But it should be understood that this is what some lifters think, not what is actually occurring.

An approach that I have found to be much more effective in correcting a “reverse curl” kind of pull is one taught to me by Joe Mills. The Mills method was essentially to have the lifter run his or her thumbs along the front of the torso and to flip the hand over to a palms up position at the end. This movement is extremely simple and can be executed with great speed after very little practice. It teaches the lifter that the hands need not travel in front of the body (as compared with along it) in order for the hands and elbows to turn over quickly, although the elbows do necessarily go behind the bar during this process. Naturally the position cannot be precisely duplicated with the bar, because the bar will remain in front of the lifter to a certain extent. However, the lifter will quickly feel how close the bar could be and that the reverse curling motion is unnecessary and inappropriate.

With the bar, the lifter must concentrate on whipping the elbows fast and high (above the level of the shoulders if possible, to the same level at least). Most coaches and athletes understand that speed in the elbow whip is essential, so that the lifter keeps the elbows away from the knees while going under the bar and settling into the rack position. They recognize that in the clean a high elbow position in the squat helps the lifter to maintain an upright position, with the back (particularly the upper part) properly arched. Therefore, good coaching leads to assuming the correct position in the squat and to assuming it quickly. However, what is often overlooked by coaches is that the speed and force of the elbow whip are important in maximizing the lifter’s speed in descending under the bar and therefore are of immense help in improving the efficiency of the lifter’s clean. When a very forceful elbow whip is executed, it requires a powerful contraction of the shoulder muscles (which drives the elbows up). The elbows and shoulders create an equal and opposite downward force on the lifter’s body, driving the body down under the bar. Dave Sheppard intuitively recognized this principle when he told me and many others over the years to “whip the elbows like mad.” Dave had one of the fastest and greatest cleans in the sport of weightlifting, no doubt due in part to his commitment to elbow speed.

One last point on the subject of elbow whip: when a lifter has a shoulder width grip, thinking of pushing the elbows up is sufficient to get the elbows to a position of maximum height with maximum speed. However, when the grip is significantly wider than the shoulders, the lifter must think of pushing in as well as up with the elbows (i.e., think of pushing the elbows toward one another as well as up). This little trick, which was taught to me by a fine lifter named Mark Gilman, has enabled many who have tried a wide grip but have been unable to get the elbows up to master the elbow whip with a wide grip after a little practice.

Trade-free fitness at myworkoutarena.com

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to react!