The Importance of the Position and Effort in the Final Explosion

Although the position of the body and the bar is crucial throughout the lift (particularly because an incorrect position in any part of the lift often creates a tendency to assume incorrect positions at later stages), the position just prior to the final explosion is perhaps the most crucial. If that position is off, it almost assures that difficulties will arise during the amortization and recovery phases. Therefore, both athlete and coach should devote a significant share of their attention to this issue. What is the correct position?

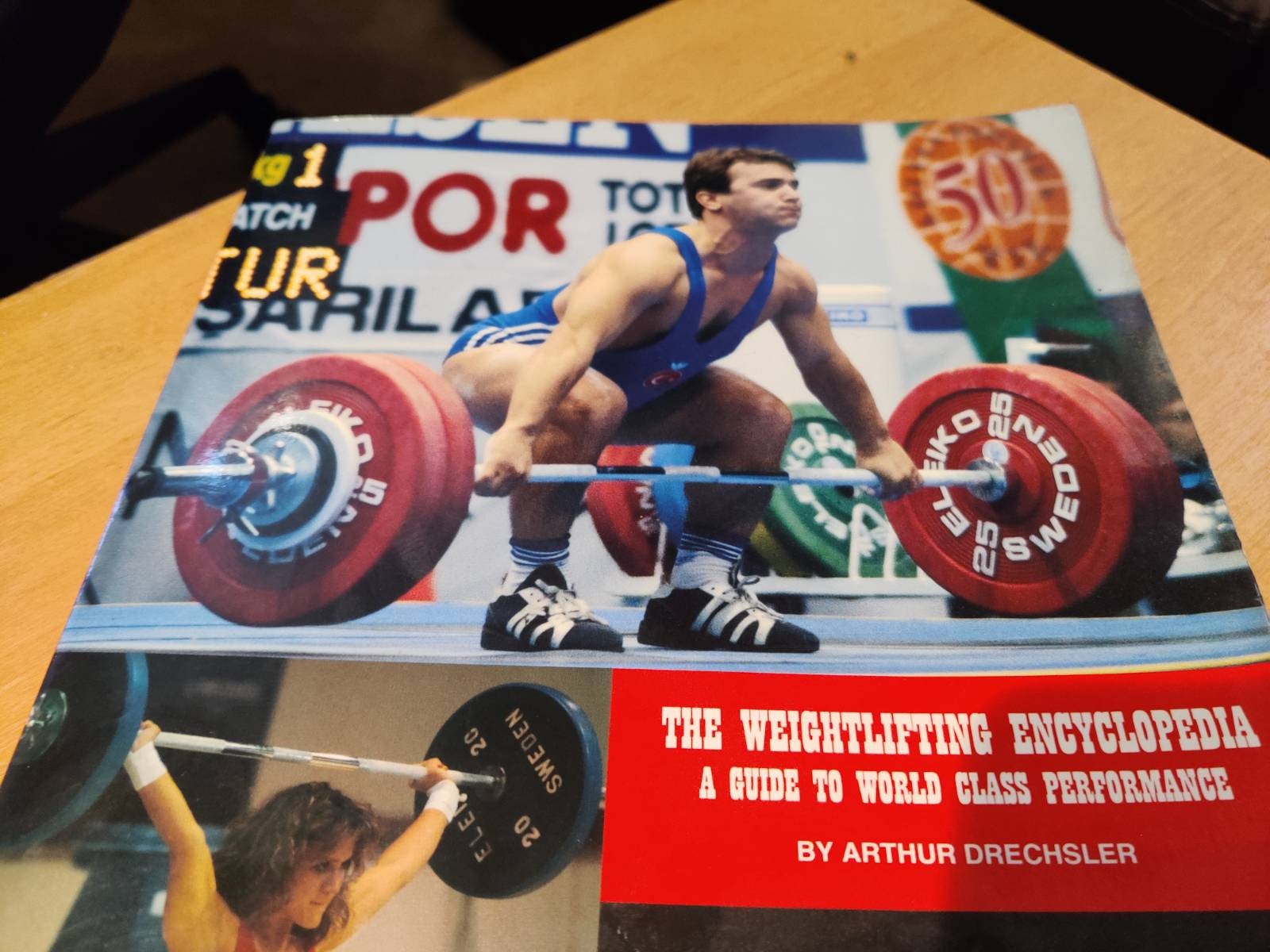

It is a position with the shoulders directly above the bar (not significantly in front of it or behind it, when viewed from the side): the arms straight or nearly so; the outside of the elbows turned to the side and not toward the back; the knees well bent (sometimes the athlete is beginning to rise on the toes as well); the back flat or arched; and the shoulders back but not yet shrugged upward (see the 3rd photo in the sequence in Figure 3). Ideally, the lifter’s balance is toward the front of the full foot; if the lifter’s balance is significantly toward the rear at this stage, the lifter will necessarily accelerate the bar in a rearward as well as an upward direction during the explosion. This wastes energy (a straighter bar trajectory is more efficient) and causes an excessive degree of bar motion that will be difficult to control when the bar is caught (i.e., excessive horizontal motion). As the lifter rises on the toes, shoulders, the base of the toes and the bar should line up vertically; mispositioning of the shoulders relative to the bar at this point reduces the ability of the athlete to exert maximal force and increases the likelihood that the bar will be directed further forward or backward than is optimal.

Regardless of whether the athlete pulls as quickly as possible during the entire pull or accelerates during the later phases, the lifter must make a special effort to apply a maximal explosive force to the bar at the beginning of the final explosion of the pull. This explosive effort serves to accelerate the bar, raising it and giving the athlete time to squat under the bar. Most lifters find it helpful to think of an explosive effort with the leg, hip and back extensors. Some coaches talk about “hitting” the bar with the traps at the last stage of the final explosion. Others talk of a jumping motion with the bar in the hands and an explosive shrug

Many lifters think of making violent contact with the bar at the level of the thighs or hips at the finish of the pull; some lifers make such an effort to “hit” the bar explosively with the hips that they wear a pad over their pubic bone-arguably an illegal piece of equipment. While this works for some lifters, it has been my experience that significant contact with the thighs or hips can misdirect the bar, particularly when it is intentional. When the lifter is thinking of an explosive extension of the legs, hips and back, the noticeable contact of the bar against the lifter’s body occurs as a result of the rapid extension. If the contact occurs as a result of a conscious effort to hit the bar with the body, the lifter has wasted valuable energy and attention on a horizontal rather than vertical motion. There is horizontal motion of the hips and back during the explosion phase of the pull, to be sure, but, it is much more beneficial when that motion is a result of an effort to explode upward than when the objective is to move the hips or thighs forward into the bar (or to move the bar back into the hips).

There are, however, exceptions to the preceding guidelines. Some lifters have a tendency to extend the trunk upward and backward, with their hips held in a stationary position during the final explosion of the pull. These lifters actually seem to freeze the position of the hips and to simply rotate the trunk around that fixed point. Clearly this can lead to a horizontal misdirection of the bar. For such lifters, the instruction to drive the hips forward at the finish of the pull will often lead to a correction of the problem caused by the rotation of the trunk around fixed hips and will result in the lifter effecting the proper combined contraction of the leg, trunk and hip extensors.

Explosiveness and following a proper sequence in the use of the athlete’s muscles go hand in hand in making the final acceleration phase of the pull as effective as possible. This is because a lack of explosiveness or an improper sequence of muscle utilization will result in less than optimal acceleration. The proper sequence is legs and back together, followed by the calves and the muscles of the shoulder girdle (the arms are not really used at all during the acceleration phase of the pull). Although the combined action of the muscles of the shoulder girdle and the calves follows that of the legs, hips and torso, they do not wait until the action of the first set of muscles has ceased. Rather, the contraction of the calf and trapezius muscles begins while the legs and hips are finishing their effort, so that there is a continual application of force.

One final point should be made about the final explosion phase. From the 1950s through the 1970s, much discussion appeared in the weightlifting literature regarding the importance of fully stretching the body at the end of the final explosion phase of the pull. Athletes were pictured on their toes like ballerinas, with the legs fully locked-the more extreme the stretch the better. As more modern methods of technique analysis became available, research findings disclosed that the power developed by the lifter at the point before the legs were locked and the lifter rose high on the toes was primarily responsible for the ultimate height attained by the bar. The force applied by the lifter in the extended position was far less important. Moreover, it was discovered that many elite lifters did not lock their legs completely at the end of the final explosion. This failure to lock the legs meant that the lifter had a shorter distance to drop under the bar after the completion of the final explosion and it enabled them to drop faster (spared the time of unlocking the legs while squatting under). It has been rumored that Soviet researchers have also discovered that a snap of the legs to a completely straight position at the end of the final explosion causes the feet to be displaced in a rearward direction just after the final explosion-still another reason to avoid the legs locked position. This in no way means that the lifter should straighten the legs at the end of the final explosion stage; it merely means that being rigidly locked high on the toes may have negative consequences that offset any advantages of an extreme stretch of the body.

In view of the complexity of the above considerations, a specific lifter’s approach to the body’s position in the final extension needs to be worked out on the basis of individual needs and through experimentation.

Trade-fitness at www.myworkoutarena.com

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to react!